There’ve been a lot of headlines recently about vaccine mandates and the number of police officers around the country who are choosing to retire or resign rather than disclose their vaccination status to their superiors, but the prospect of further police shortfalls in cities like Chicago and Baltimore (where only about 2/3rds of uniformed officers have disclosed their vaccination status) could be compounded by the fact that in several big cities, the number of prosecutors available to take on cases once arrests have been made is steadily declining.

Byron Warren can’t find enough hours in the day. Not when he’s responsible for prosecuting 120 felony cases in Baltimore.

The assistant state’s attorney works evenings and weekends to keep up with motions, trial preparation and witness interviews. That’s not counting his days in the courtroom. The 33-year-old feels like he’s back in college and going through the wringer to join a fraternity.

“It feels like a pledge process that never ends,” he said. “It means no work-life balance.”

Resignations at the office of Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby have left prosecutors such as Warren with crushing caseloads. The number of assistant state’s attorneys — the people who prosecute crimes in the city — has declined 24% over the past three years from 217 to 164, according to the office.

They’re walking out for private practice or the suburbs, where they have lighter workloads and a chance for higher pay. Stress and the demands of the job have always brought turnover, but the coronavirus pandemic worsened matters. The courts reopened after 18 months with a backlog of thousands of felony cases.

The Baltimore Sun goes easy on Marilyn Mosby, though I can’t help but wonder if her own legal troubles have had anything to do with the fact that a quarter of the prosecuting attorneys in her office have fled over the past three years.

I’m also curious to know if any of these departures were the result of a difference in opinion about how zealously offenses should be prosecuted in Baltimore. Mosby has recently touted her office’s conviction rates, but critics say the prosecutor hasn’t been nearly as forthcoming about the number of cases her office has decided to drop.

“Reviewing the data that has been provided by the State’s Attorney for Baltimore City is like looking at an old baseball card with none of the statistics on the back,” said Jeremy Eldridge, a defense attorney who was once prosecutor in the City State’s Attorney’s Office.

Eldridge believes what’s missing is how many cases were ultimately dropped by the SAO or were pleaded down to less serious charges.

“If you can’t see the number of jury trials that actually go to trial as opposed to being pleaded down to other offenses and if you’re not seeing the number of cases that are being dismissed, you’re really not getting a true and clear picture of what the prosecution in this city looks like,” Eldridge said. “It matters because, if you’re looking at violent repeat offenders, are these individuals being prosecuted for the crimes that would actually be assisting the public in assuring that violence doesn’t continue?”

That’s a good question, but one that Mosby hasn’t been able (or willing) to answer. One thing we do know, however, is that the phenomenon of fleeing prosecutors isn’t limited solely to Baltimore. In fact, in San Francisco some newly-departed prosecutors are now aiding the effort to recall District Attorney Chesa Boudin.

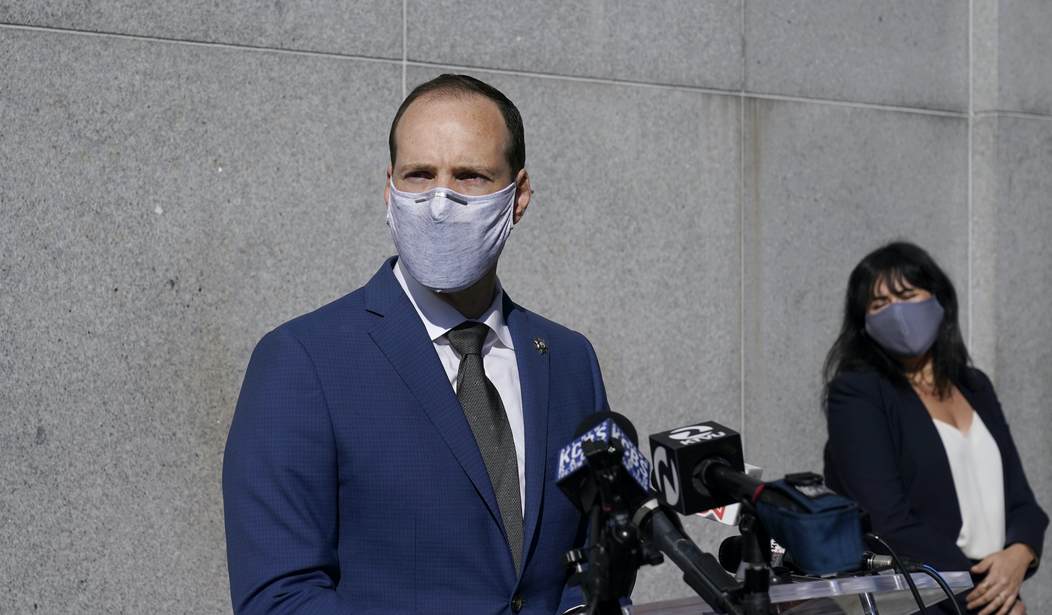

Prosecutors Brooke Jenkins and Don Du Bain tell the NBC Bay Area Investigative Unit they have quit their jobs at the San Francisco District Attorney’s office and joined the effort to recall their former boss, District Attorney Chesa Boudin.

They are among at least 51 lawyers at the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office who have either left or been fired since Boudin took office in January 2020, according to documents obtained by the Investigative Unit – that’s about a third of the department’s attorneys now gone.

“Chesa has a radical approach that involves not charging crime in the first place and simply releasing individuals with no rehabilitation and putting them in positions where they are simply more likely to re-offend,” Jenkins said.

The now-former prosecutors say that Boudin is disregarding the laws and court decisions that he disagrees with and is instead imposing “his own version of what he believe is just”; a vision that is too far out there even for many in the San Francisco area.

Jenkins and du Bain point to specific cases:

In one case, a man charged with robbery, who had eight prior felony convictions, was released early by the district attorney. He was then arrested four more times for other crimes, but the district attorney’s office never charged him. Then, nine months after he was set free, he hit and killed two women while driving a stolen car, drunk.

“The fact that killers may go free, just doesn’t sit very well with me,” said Jenkins, who spent seven years prosecuting cases in the district attorney’s office, most recently serving in the department’s homicide unit, taking on the city’s most violent criminals.

In another case, prosecutor Don du Bain said Boudin ordered him to request a more lenient sentence for a man who was convicted of shooting his girlfriend in the stomach. The request, du Bain argues, would have been a violation of state statutes, which govern criminal sentences. As a result, du Bain said he withdrew from the case.

The reasons behind the disappearing prosecutors in San Francisco and Baltimore may not exactly jibe with each other, but I suspect that there are some commonalities at play in Boudin and Mosby’s offices: a soft-on-crime approach, a belief that law enforcement does more harm than good, and a greater emphasis on non-incarceral consequences instead of ensuring that violent offenders receive serious prison time for their crimes.

There’s another commonality: a rising homicide rate in both cities. In San Francisco, murders are up over 7% compared to 2020, while Baltimore is on pace for its seventh straight year of 300+ homicides. With fewer prosecutors to handle these cases and chief prosecutors who have been accused of going light on defendants, don’t expect these dismal numbers to change direction anytime soon.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member