Honestly this is a fairly settled point by now, at least when it comes to the courts, but to the anti-gun crowd nothing about our right to keep and bear arms is set in stone. Not even multiple Supreme Court decisions are enough to end the debate over what the scope of the Second Amendment’s protections, or even whether the Second Amendment protects an individual right at all.

Louisville Courier-Journal opinion editor and Creators Syndicate columnist Bonnie Jean Feldkamp is one of those professing continued confusion about the Second Amendment, and in her latest column claims that “in order to develop solutions to mass shootings in this country, we must first establish a foundation of fact that everyone can agree on”, starting with how to define the “arms” that we have a right to keep and bear.

What law, if it had been passed prior to the mass shooting, would have prevented it from happening, while at the same time preserving the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms?

As a reminder, the Second Amendment simply reads, “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

So, the answer I keep coming up with for this question is that it depends on how you define “arms.” Google defines it this way: “weapons and ammunition; armaments.” But what does that mean when it comes to the rights of responsible gun owners? An agreed-upon definition is important because without a common understanding of what we’re talking about, we cannot begin to have productive conversation around gun policy and legislation while also protecting Second Amendment rights.

Another protest I tend to hear is that gun laws are a “slippery slope” and that once we start banning one type of weapon, it’s only a matter of time before others are taken away and our rights are increasingly infringed upon. But the truth of the matter is that we already have weapons bans. There are arms that are already illegal in America — fully automatic weapons and sawed-off shotguns and rifles, for example. Nuclear weapons are banned. Switchblade knives are also illegal. I would consider all of these in the “arms” category. I don’t hear a lot of arguments over illegal grenades and bombs, though. Some arms are rightfully out of reach for everyday civilians, and it seems we can all agree on that point.

Contrary to Feldkamp’s claims, machine guns are not illegal in America, though their purchase and possession is heavily restricted and no new machine guns have been available to the public since the Hughes Amendment was adopted in the 1980s. As for switchblades, they’re certainly not banned at the federal level, at least not outside of Native American reservations and U.S. territories. At the state level, switchblade bans have been disappearing thanks to the efforts of groups like Knife Rights, which filed a federal lawsuit just last month taking on California’s ban on switchblades.

But we also have a definition of “arms” to work with; one provided by the Supreme Court in the Heller case back in 2008. Here’s what SCOTUS said at the time:

The 18th-century meaning is no different from the meaning today. The 1773 edition of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary defined “arms” as “weapons of offence, or armour of defence.” Dictionary of the English Language 107 (4th ed.) (hereinafter Johnson). Timothy Cunningham’s important 1771 legal dictionary defined “arms” as “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another.” A New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771); see also N. Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) (reprinted 1989) (hereinafter Webster) (similar).

The term was applied, then as now, to weapons that were not specifically designed for military use and were not employed in a military capacity. For instance, Cunningham’s legal dictionary gave as an example of usage: “Servants and labourers shall use bows and arrows on Sundays, &c. and not bear other arms.” See also, e.g., An Act for the trial of Negroes, 1797 Del. Laws ch. XLIII, §6, p. 104, in 1 First Laws of the State of Delaware 102, 104 (J. Cushing ed. 1981 (pt. 1)); see generally State v. Duke, 42 Tex. 455, 458 (1874) (citing decisions of state courts construing “arms”). Although one founding-era thesaurus limited “arms” (as opposed to “weapons”) to “instruments of offence generally made use of in war,” even that source stated that all firearms constituted “arms.” J. Trusler, The Distinction Between Words Esteemed Synonymous in the English Language37 (1794) (emphasis added).

Some have made the argument, bordering on the frivolous, that only those arms in existence in the 18th century are protected by the Second Amendment. We do not interpret constitutional rights that way. Just as the First Amendment protects modern forms of communications, e.g., Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U. S. 844, 849 (1997), and the Fourth Amendment applies to modern forms of search, e.g., Kyllo v. United States,533 U. S. 27, 35–36 (2001), the Second Amendment extends, prima facie,to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not in existence at the time of the founding.

That takes care of nuclear weapons and hand grenades, and it also means that modern sporting rifles are protected as well, given that they’re bearable arms not specifically designed for military use nor employed in a military capacity. Of course, Feldkamp sees it differently.

The semi-automatic AR-15 was designed for the military in the 1950s but is now considered the civilian counterpart to the fully automatic M-16 military weapon that gave soldiers an advantage over the AK-47 in combat. If one military-grade weapon is available to the general public, then why not other weapons designed for war? If you can buy an AR-15-style as a civilian without any kind of training or licensure, why not a hand grenade?

Remember what the Court said about arms; weapons not specifically designed for military use and not employed in a military capacity. Well, the AR-15s and other modern sporting rifles that are among the most popular arms sold in the United States today were not specifically designed for the military and are not broadly used in a military capacity, unlike their select-fire cousins.

I go back to my original question. What does it mean to have the right to “bear arms” in the United States? Which arms fall within those rights? Does requiring training, licensing and insurance, like we do for motor vehicles, infringe on our Second Amendment rights?

It’s seemingly wide open for interpretation, leaving Americans with no clear understanding of where the line should be drawn. If we can save the soapbox buzzwords and the bickering, perhaps having meaningful conversations around what the language of the amendment means might be a good place for our leaders to start. Congress should provide America with a working definition of what it means to “bear arms.” Then maybe we can set aside thoughts and prayers and begin to have productive discourse that produces solutions and saves lives.

Why would Feldkamp think that a divided Congress would provide her with the definition she wants any more than the courts have? The truth is out there, it’s just that Feldkamp doesn’t want to acknowledge it. The Supreme Court has already told us what the definition of “bear arms” is. Again, from the Heller decision:

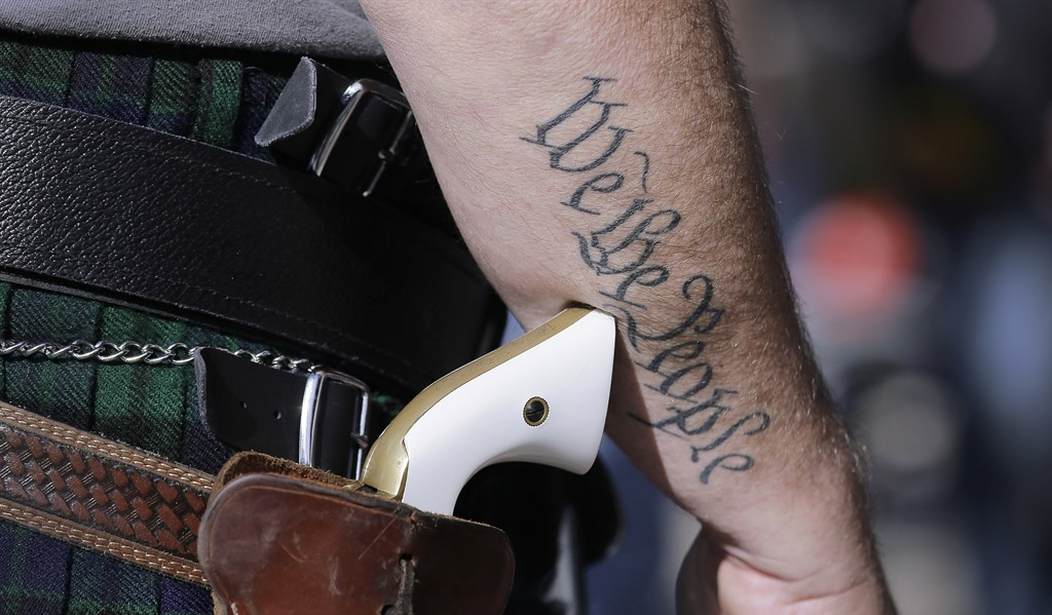

At the time of the founding, as now, to “bear” meant to “carry.” When used with “arms,” however, the term has a meaning that refers to carrying for a particular purpose—confrontation. In Muscarello v. United States, 524 U. S. 125 (1998), in the course of analyzing the meaning of “carries a firearm” in a federal criminal statute, Justice Ginsburg wrote that “[s]urely a most familiar meaning is, as the Constitution’s Second Amendment … indicate[s]: ‘wear, bear, or carry … upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose … of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.’ ” Id., at 143 (dissenting opinion) (quoting Black’s Law Dictionary 214 (6th ed. 1998)). We think that Justice Ginsburg accurately captured the natural meaning of “bear arms.” Although the phrase implies that the carrying of the weapon is for the purpose of “offensive or defensive action,” it in no way connotes participation in a structured military organization.

… Putting all of these textual elements together, we find that they guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation. This meaning is strongly confirmed by the historical background of the Second Amendment. We look to this because it has always been widely understood that the Second Amendment, like the First and Fourth Amendments, codified a pre-existing right. The very text of the Second Amendment implicitly recognizes the pre-existence of the right and declares only that it “shall not be infringed.”

If Feldkamp is confused about what the right to keep and bear arms really means, it sounds like willful ignorance on her part. The Supreme Court has already provided us with a definition. She may not like what the Court has said, but there shouldn’t be any confusion about what they meant or what the Second Amendment actually protects.