I understand that, for many New Yorkers, the idea of carrying around a gun for self-defense sounds utterly bizarre, especially since the state has made it so difficult for the average citizen to do so. Still, an argument by the editors of the Long Island paper Newsday is off target in arguing that the “culture shock” that would come with a Supreme Court opinion striking down the state’s “may-issue” licensing laws for carry permits.

Tough restrictions on the ability of New Yorkers to legally carry guns in public have been embedded in local habit and practice for more than a century. Through periods of high and low crime rates, local elected officials knew they had consensus support when speaking of “getting guns off the streets” and “taking guns out of the hands of criminals.”

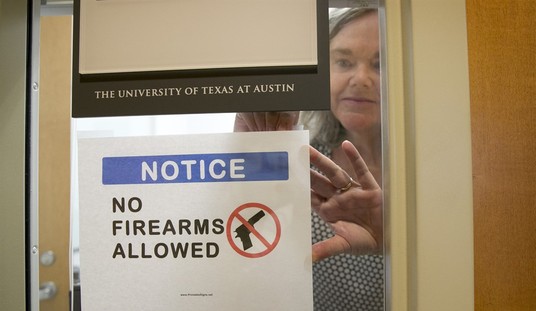

Adults throughout the region know about the high bar for permission to carry a registered pistol unless they have worked in law enforcement. Not only does it take many months to get an application approved or denied in Nassau and Suffolk counties and New York City, but every law-abiding resident must show “proper cause” for the license to walk around outside the home with a concealed handgun. That’s why few people are known to do so.

Now a measure of culture shock may be coming. The U.S. Supreme Court announced Monday it will consider a constitutional challenge claiming New York law “makes it virtually impossible for the ordinary law-abiding citizen to obtain a license,” allegedly in violation of the Second Amendment.

Looking ahead, Long Island will have its gun clubs, hobbyists and shooting ranges no matter what. But our general lifestyle currently carries an official assurance that most of the time, the stranger we encounter at the mall, in the street, or coming from the ballgame won’t be packing a Glock 26 without a carefully-issued license.

If the court ends that assurance, residents who didn’t feel the need to tote a concealed piece before might find it logical to get one. More carried weapons could complicate other public-safety debates roaring across the land, from how to stem mass shootings to how police interact with communities.

I’m sure it would be a culture shock in parts of New York if the state were compelled by the Supreme Court to adopt a “shall issue” system for concealed carry licenses. It was a culture shock in the south when schools were forced to integrate back in the 1950s and 60s as well, but since the dominant culture was abusing and infringing on the civil rights of others, the Court stepped in.

New York’s “may-issue” licensing laws are also part of the dominant culture in the state, but that doesn’t mean that they’re a good thing. These policies are also leading to the abuse and infringement of a civil right, and in fact the state’s licensing laws for possession and carriage of firearms were put in place a century ago by the powerful and elite business class in the state in an attempt to crack down on “undesirables” carrying guns.

The Sullivan Law was born out of a set of circumstances eerily similar to our own recent history. On August 9, 1910, William Gaynor, the popular Democratic mayor of New York City, was shot in the neck as he waited to board a steamship in Hoboken, New Jersey. His assailant, a disgruntled New York dockworker named John J. Gallagher, was immediately wrestled to the ground by bystanders and quickly taken into police custody. Gaynor, who insisted he was well enough to embark on his vacation, was rushed to a nearby hospital and patched up by a team of surgeons who proclaimed his condition stable.

In the weeks that followed, journalists and social critics struggled to make sense of what seemed to be such senseless violence. Some observers attributed the whole affair to mental illness, arguing that Gallagher was crazy and that his crime was no more than the confused, tragic outburst of a madman. Others disagreed, asserting that the attempted assassination was a symptom of a diseased society. Gallagher, these progressives insisted, was the unadulterated embodiment of America’s selfish national culture. Even the recovering Gaynor chimed in, blaming the attack on the vitriolic yellow press—particularly the sensationalist Hearst newspapers—that had poisoned the populace against him…

But in the winter of 1910 and the spring of 1911, the two tales diverged as a new explanation for the shooting emerged and gained valuable converts amongst New York’s political elite. The problem was handguns, the public’s infuriatingly easy access to small, concealable handguns! That was the message put into the papers by the Legislation League for the Conservation of Human Life, that was the message campaigned on by State Senator Timothy D. Sullivan, the burly and infamous Tammany Democrat, and that was the message supported by 46 (of 51) senators and 123 (of 130) assemblymen who voted for a bill that would make it illegal for any individual to purchase a handgun without a police-issued license in the state of New York. The Sullivan Law, as it was known, took effect September 1, 1911.

The first person convicted under New York’s Sullivan Act was an Italian immigrant named Marino Rossi, who was busted with a handgun on his way to a job interview. Rossi had no intent to commit a violent crime with his gun. He was merely carrying for self-defense, but that didn’t matter to the judge, who sentenced Rossi to a year in prison.

These days, carrying a gun without a license in New York can lead to a 3 1/2 year prison sentence, but the wealthy and elite are still largely immune from the law’s effects. Instead, it’s mostly young black men without serious criminal histories who are arrested and charged with violating the Sullivan Act. Is this a cultural artifact worth preserving? I’d argue no, but the editors at Newsday are apparently okay with these discriminatory laws and the culture that finds them acceptable.