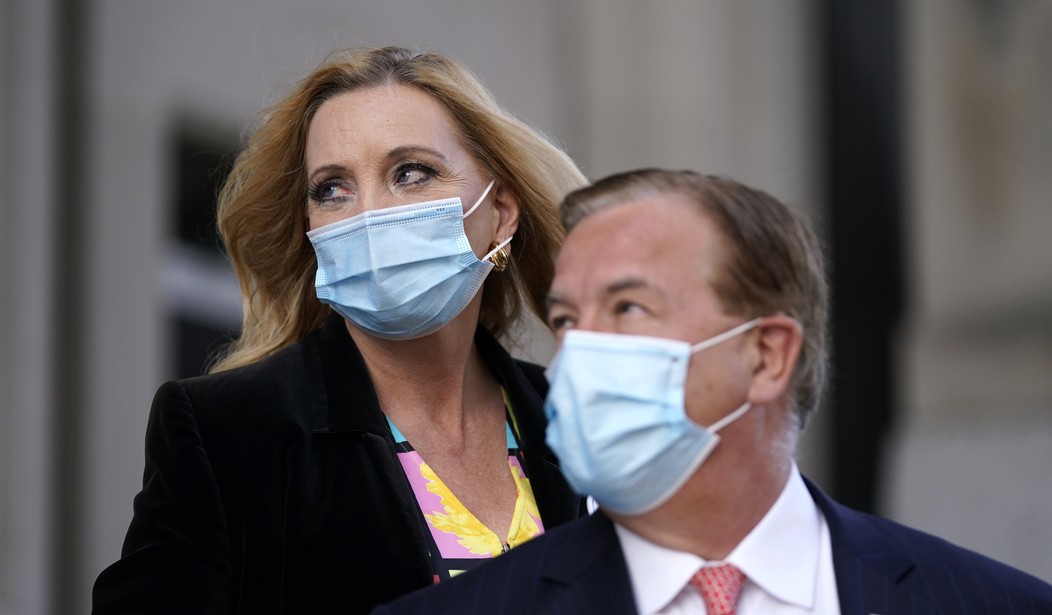

When Mark and Patrcia McCloskey decided to avoid a trial on felony unlawful use of a weapon charges and instead plead guilty to a lesser misdemeanor, one of the provisions of their deal was that they would forfeit the firearms they displayed last summer as scores of protesters marched through their private St. Louis neighborhood. Now that Missouri Gov. Mike Parson has officially pardoned the pair, however, Mark McCloskey is seeking the return of their guns, along with the fees the couple forked over as part of their plea agreement.

McCloskey sued Wednesday in St. Louis City Circuit Court, citing the pardon in demanding Missouri give back a Colt AR-15 rifle and Bryco pistol.

In his petition, McCloskey writes that the pardon absolved him of “all wrongdoing” and nullifies all judgments and orders in the case. He is also seeking to have fines against him repaid.

“The politically-motivated charges that were used to seize our guns were dropped and now the Governor has granted both Patty and me pardons,” Mark McCloskey said in a statement. “I filed a lawsuit today to demand that the Circuit Attorney return our guns immediately.”

According to the Missouri Department of Corrections, a full pardon removes any “punitive collateral consequence stemming from the conviction without conditions or restrictions.”

McCloskey is representing himself in this latest case (you can read his initial complaint here), and my non-lawyer take is that he appears to have a pretty good case. If a pardon does indeed remove all punitive collateral consequences of the original conviction, that would seem to apply to the forfeiture of firearms as well as the fines that the McCloskeys paid.

I believe that Parson’s pardon was appropriate, and I hope the McCloskeys are successful in regaining possession of their firearms, particularly since they never should have been charged with a crime to begin with. But now that the Missouri governor has taken care of this particular case I also hope he’ll turn his attention to several other individuals who could use a pardon as well.

Kevin Strickland, Christopher Dunn, and Lamar Johnson all have something in common: they all have spent decades in the Missouri prison system, they all maintain their innocence, and the cases that led to their convictions have all fallen apart. Yet the men remain behind bars with no release in sight despite various government actors suggesting they should have their verdicts overturned.

Do yourself a favor and read Billy Binion’s entire story at Reason, which documents in great detail the Kafka-esque bureaucratic nightmare that’s kept them behind bars even after prosecutors and judges have agreed that they shouldn’t be in prison. Dunn, for example, was convicted of murder in 1991 solely on the testimony of two juveniles who later say they were coerced by authorities to point their finger at the then-18-year old, and a judge said last year that he doesn’t believe any jury would convict Dunn based on the current lack of evidence and Dunn’s alibi in the case.

Johnson and Strickland’s cases are even more absurd, in that prosecutors agree they are innocent. “My job is to apologize” to Strickland, said Jackson County prosecutor Jean Peters Baker at a press conference in May. “It is important to recognize when the system has made wrongs…and what we did in this case was wrong. So, to Mr. Strickland, I am profoundly sorry.”

Now 62, Strickland was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in 1979 for a triple-murder that took place the year prior in Kansas City. He has had several heart attacks and sometimes needs a wheelchair.

Strickland’s conviction was also circumstantial, hinging on testimony from a woman named Cynthia Douglas, who picked him from a lineup. She, too, later recanted and said that police had pressured her to select Strickland. His first trial ended in a hung jury, and he was convicted on the second go-round.

“I think I’ve been destroyed,” Strickland told the local ABC affiliate in June. “I’ve been placed in an environment where I had to adapt to living with all sorts of confessed criminals. The way I see things now is not normal, I would think, for somebody in society.”

St. Louis prosecutor Kim Gardner zeroed in on Johnson’s case two years back and sought to have him released. Convicted of the 1994 murder of Marcus Boyd, the 49-year-old’s story follows a familiar arc: A jury delivered their verdict based only on testimony from a witness who later recanted, admitting police had paid him for his services.

Taking up Johnson’s case may be one of the few things that Gardner’s done right in her time as St. Louis Circuit Attorney, though her involvement probably hasn’t helped persuade Republican Attorney General Eric Schmitt or Gov. Parson to do the same. Given the circumstances that led to the convictions of these three men, however, it sounds to me like a pardon by Parson would be appropriate.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member