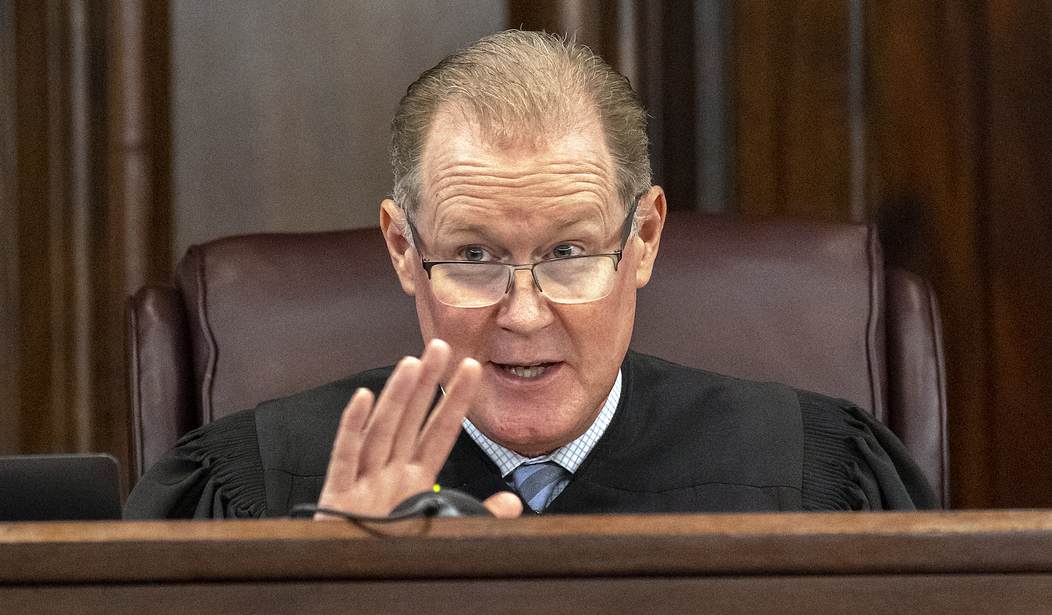

I missed attorney Andrew Branca’s thread on Judge Timothy Walmsley’s instructions to the jury when it was posted on Tuesday, but now that the jury has returned guilty verdicts against all three men accused of murdering Ahmaud Arbery, the topic is even more germane. After all, Travis and Gregory McMichael, along with co-defendant William “Roddie” Bryan are almost certain to appeal their convictions, and arguing that the judge inaccurately informed the jury about the citizens arrest law that the men say gave them the right to pursue and detain Arbery on the day of his death is a compelling one.

Here’s Branca’s argument about why Judge Walmsley got it wrong.

The amount of ambiguity in the statute is really remarkable if only because of the statute’s brevity—it is only two sentences long. Those two sentences are:

A private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.

My own reading of that statute, applying normal rules of statutory construction, is that the two sentences present two different scenarios for a citizen’s arrest. The second sentence refers explicitly to a felony scenario and sets out certain requirements for that scenario that differ from the requirements set out in the first sentence. My reading is that the first sentence is therefore contemplating the alternative criminal scenario, the non-felony, the misdemeanor.

So, if the citizen’s arrest is being made for a serious felony, like murder, the person making the arrest is required to have reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion, which Judge Walmsley is interpreting as probable cause. Fair enough.

If the citizen’s arrest is being made merely for a misdemeanor, however, then probable cause is not enough. After all, an arrest is a real burden on a person’s personal liberty, and ought not be done lightly

Before we’ll allow a citizen’s arrest for a relatively minor crime, then—imagine shoplifting, for example—we’ll require more than just probable cause, we’ll require that the offense was committed in the presence of the person making the arrest, or that they have immediate knowledge of the offense (perhaps observed from a distance, for example).

So, my reading of this citizen’s arrest statute is that the first sentence refers to arrests premised on a misdemeanor offense, and the second sentence refers to arrests premised on a felony offense.

… in any case, however, at the end of the day, the question of how this law is to be applied in this criminal trial is not up to me, and it’s not up to ADA Dunikoski

And most definitely of all, it’s absolutely not up to the jury, whose job is to be the finder of fact, to work through any ambiguity of evidence—not to work through the ambiguity of law.

The person in charge of the law in a trial is the judge—in this case, Judge Timothy Walmsley. It is his duty to decide how the law is to be applied to the facts as the jury determines those facts to be proven or not proven.

And this Judge Walmsley abjectly failed to do. And in a trial with three defendants looking at life in prison, that’s a contemptible professional failure.

Remember—the key issue is whether the two sentences in the citizen’s arrest statute are intended to be melded together so that both apply to all arrests, or whether the conditions of the first sentence refer to misdemeanor arrests and the conditions of the second sentence refer to felony arrests.

That’s the fundamental issue that Judge Walmsley needed to resolve.

And he did not.

At no point does the Judge tell the jury whether they are to treat the two statutory sentences as both applying in all arrests, or whether the separate felony conditions are to be independently applied in the case of an arrest predicated on a felony offense.

So with all the legal experts in that courtroom—three attorneys for the State, and apparently 6 attorneys for the defense, plus Judge Walmsley—we are going to leave the fate of these three defendants to however the jury decides to interpret an ambiguous statute that appears to befuddle even the experts.

It’s ridiculous.

In fact, Branca goes on to label the judge’s actions on Tuesday “contemptible,” highlighting one key passage from the judge’s jury instructions:

The private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony, and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.

Branca says that “it was the duty of Judge Walmsley to decisively construct a non-ambiguous jury instruction from this ambiguous statute,” and that he failed to do so.

Now, Andrew Branca has likely forgotten more self-defense law than I’ll ever know, but after listening to the judge’s instructions (you can view the relevant portion in the video window below), I thought the instructions were fairly straightforward, even if the citizens arrest statute itself contained some ambiguity.

Here’s what Judge Walmsley told the jurors after the passage that Branca highlighted.

A private citizen’s warrantless arrest must occur immediately after the perpetration of the offense, or in the case of felonies, during escape. If the observer fails to make the arrest immediately after the commission of the offense or during escape in the case of felonies, his power to do so is extinguished.

In other words, according to Walmsley’s interpretation of the law in question, the only time that you’re allowed as a citizen to make an arrest is at the time the crime has been committed or (if we’re talking about a felony), if the person is trying to escape being arrested. I agree with Branca that the law itself was confusing (which is one of the big reasons why it’s since been repealed), but I don’t see how it could have ever applied to the McMichaels that day.

The men had no direct or immediate knowledge that Ahmaud Arbery had committed even a misdemeanor offense that day when they began their chase. And to this day there’s no evidence that Arbery committed a felony on the day he was killed or any other. One of the officers who’d previously spoken to Gregory McMichael about people wandering through the unfinished home of his neighbor told jurors that if he had been able to determine that Arbery was one of the individuals captured on surveillance video, he would have given him a warning that he was trespassing, which is a misdemeanor and not a felony under Georgia law.

Again, I’m not the legal expert that Andrew Branca is, so if he believes that Judge Walmsley’s instructions to the jury were unclear and ambiguous, I’ll take him at his word. I just don’t see any reading of the since-repealed citizens arrest law that would have empowered the McMichaels and Bryan to legally detain Ahmaud Arbery that day, at least based on the evidence that was presented during the trial.