Among the many flaws with Extreme Risk Protection Orders, also known as “red flag” laws, is the fact that even though a judge may determine someone to be a danger to themselves or others, there’s no mental health treatment offered to the individual in question. Instead, any legally-owned guns they might possess are taken away, along with their legal ability to acquire another, but the underlying mental health issue remains unaddressed and untreated.

You’d think it would be simple enough for the lawmakers who write “red flag” laws to impose some sort of mental health treatment as part of the process, but in state after state over the past few years legislators have approved ERPO laws that are missing what should be a key component of any measure supposedly designed to protect the public (and potentially the subject of the “red flag” order themselves) from harm. A recent case out of Colorado, where lawmakers are expected to dramatically expand who can file an ERPO in coming months, provides just one example of how “red flag” laws are fundamentally flawed.

Two potentially violent incidents involving a Basalt resident recently prompted a town police sergeant to file a “red flag” petition seeking a judge’s order to seize his firearms, according to court filings.

“This case is why the statute exists — to ensure that people who show a significant risk of causing harm to themselves or others don’t do it,” said Glenwood Springs lawyer Jeffrey Conklin, who also serves as Basalt’s town attorney, on Tuesday.

Since the Colorado’s Violence Prevention Act, also called a red-flag law, took effect Jan. 1, 2020, it has been used in Pitkin County courts twice, according to online data from the Colorado Judicial Branch. The Basalt case was the second instance.

…

The following timeline is based on filings in the case:

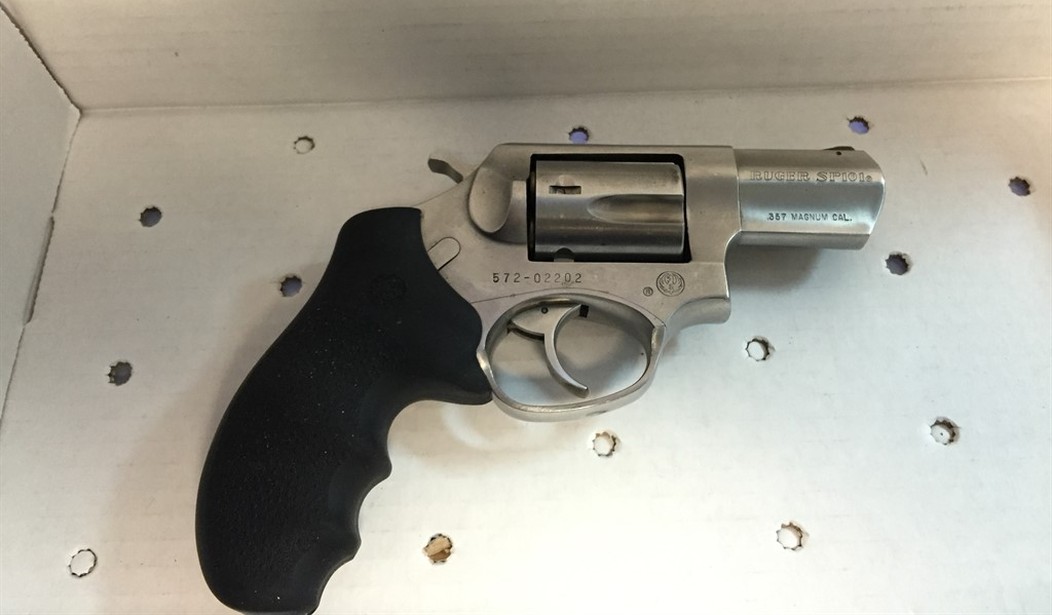

— Nov. 9, 8:05 a.m., Pitkin County dispatch received a call that a Basalt resident was at his home with a pistol to his head and threatening to take his life. “Guns were removed, and he was immediately evaluated and involuntarily committed to psyche ward on Front Range,” Santiago wrote in court filings, noting that the man and two relatives inside the home confirmed what happened. The two relatives also said the man yelled that he hated them both.

“While (the man) was being transferred to Valley View Hospital, he made a statement to the Basalt officer who was in the ambulance. The statement was something to the effect of (the man) saying he should have used the gun in a fashion that would have put police in the position to have to kill him.”

A blood draw the same day showed methamphetamines in his system. Santiago also seized his firearms.

— Nov. 16, time unknown, Basalt police responded to a report of domestic dispute where a woman locked herself in her room, “as she was scared” because the same man was showing same behavior as in the Nov. 9 incident. He also demanded that his guns be returned immediately, according to Santiago.

— Nov. 21, Santiago filed a petition and affidavit seeking a temporary ERPO in Pitkin County District Court.

— Nov. 22, a virtual hearing on the matter was held before 9th Judicial District Judge Anne Norrdin, who found probable cause that the man posed a credible threat of violence, and “there has been a credible threat of the unlawful or reckless use of a firearm” by the man, according to courtroom minutes.

Does this individual pose a legitimate risk of violence to himself or others? Quite possibly. So why is he still free to show up at the home where he threatened suicide and made a relative so fearful that she locked herself in her room to get away from him? The imposition of an ERPO hasn’t changed his behavior in any way; in fact, police say he showed up at the home a second time even after his firearms had been seized.

Just as troubling; if the suspect was involuntarily committed to a mental institution on November 9th, why was he already out just a week later?

I can only assume that, despite the news report, the individual in question was taken in on an involuntary hold for a mental health evaluation, but wasn’t actually committed to the institution by the mental health professionals who examined him, even though less than two weeks later a judge determined (without ever questioning the man directly) that he does pose a threat to himself or others. If he had been involuntarily committed he would have been prohibited under federal and state law from possessing or purchasing any firearms, making an Extreme Risk Protection Order a moot point.

Now, it could be that the mental health professionals who examined this individual truly believe that he wasn’t a danger to himself or anyone else. It could also be the case, however, that thanks to the unwillingness of Colorado lawmakers to address the state’s crisis in its mental health system, those mental health professionals waved the man away because there was no room to take him in.

A News 5 investigation found hundreds of people who are supposed to be receiving inpatient care at the Colorado Mental Health Institute at Pueblo (CMHIP) are sitting in jail awaiting a bed.

The Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS) was open, honest and transparent about a problem we discovered through a series of information requests we filed for public records and data.

Through our research, we learned county jails, the court system and State are well aware that people with a diagnosed mental illness are left sitting in a jail cell—waiting for a bed to open up at the state hospital.

…

As of early January, the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office reports 56 inmates are currently waiting on an open bed at the mental hospital.

On a state level, 347 inmates are in jail awaiting admission.

…

According to this Issue Brief from the Colorado Legislative Council Staff, under a 2012 federal settlement with the State, no defendant may wait more than 28 days for admission to the Colorado Mental Health Institute for a competency exam or restoration services. However, a review of public data shows that’s not always happening.

138 patients who have been ordered to the state hospital have been waiting in jail for more than 90 days.

CDHS cited privacy concerns for not releasing the number of inmates who have been waiting longer than a year, but a spokesperson said it’s less than 30.

Here’s a dirty little secret about “red flag” laws. The reason why there’s no mental health component to them is because that would a) cost money and b) exacerbate the existing crisis that lawmakers would prefer to ignore. Instead of treating individuals in crisis, the law simply takes their guns away and declares the problem solved when that’s clearly not the case.

Even when Democrats do bring up mental health, far too often their offering up a soundbite solution rather than any substantive programs. New York Mayor Eric Adams’ new plan to involuntary commit homeless New Yorkers, for instance, doesn’t do anything to address the fact that Bellevue and other mental hospitals in the city and state are already stretched to the breaking point. Adams is promising to take the mentally ill off the streets, but he can’t assure that they have somewhere to go.

“Red flag” laws, on the other hand, don’t even bother with trying to find help for a supposedly dangerous person in crisis. Once the guns are gone they’re on their own, with perhaps even more dangerous thoughts swirling through their head. That’s not a solution. In fact, I’d say it creates even more problems, while allowing lawmakers to escape their duty in addressing the real issues that could save lives.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member