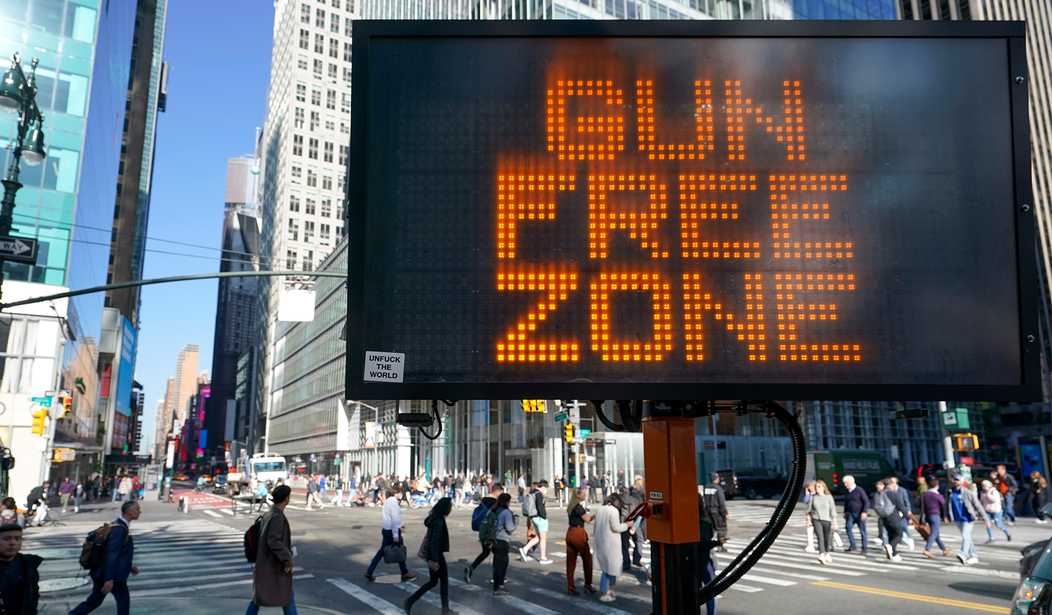

Five separate challenges to various aspects of New York’s Concealed Carry Improvement Act and recent laws aimed at gun retailers in the state got their morning in court on Monday, as a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held a series of lightning-round oral arguments touching on the large number of “sensitive places” where concealed carry is banned, whether the Second Amendment’s understanding in 1791 or 1869 should matter more to courts, the First Amendment implications of requiring concealed carry applicants to disclose their social media accounts to police, and more.

While the didn’t explicitly tell attorneys how it will rule in any of the five challenges to New York gun laws it heard on Monday morning during the hearing itself, but there were a lot of signs pointing to the judges upholding at least some of the laws in question.

J. Jacobs said that if an applicant provides the requested information, then that will make the application process go faster. In my opinion, the Anti-gun bias of this panel is starting to show at the margins. I think the panel judges have too many years of treating #2A as a… https://t.co/qzP8a0zb9J

— Mark W. Smith/#2A Scholar (@fourboxesdiner) March 20, 2023

Discussions about historical analogues. Discussions about 1791 v. 1868. Looks like 2nd Circuit may go off the rails on this point and improperly consider too late historical laws. Not terrible for 2A b/c a good appeal point if 2nd Circuit goes there. J. Jacobs trying to… https://t.co/cfPD5ADaB2

— Mark W. Smith/#2A Scholar (@fourboxesdiner) March 20, 2023

J. Lee asks about "designation" of "sensitive places" and how to figure this out. J. Lynch notes that very few of these places existed in 1791. "Were there even zoos" J. Lynch asks. J. Lynch notes SCOTUS not "giving us much to work with here." #bruenresistance

— Mark W. Smith/#2A Scholar (@fourboxesdiner) March 20, 2023

Lynch expressed his frustration with the Bruen decision at several points during the oral argument; not necessarily with the outcome (though the Second Circuit originally upheld New York’s “may issue” law before the Supreme Court overturned their decision) but with the Court’s test of history, text, and tradition. But one of the judges also appeared unaware of or willing to misrepresent what a particular justice had to say about what time period in U.S. history matters more when considering the constitutionality of a gun control law.

One judge said Barret wrote that 1868 mattered more than 1791 when she said the opposite.

Now another judge doesn't get how making social media accounts private works. https://t.co/PPkpICrH06

— Kostas Moros (@MorosKostas) March 20, 2023

1791 v. 1868 is important because there are more gun control laws to found at the state level that were enacted in the mid-19th century than in the late 1700s. It’s slightly friendlier ground for gun control activists, but Justice Barrett didn’t say that was the most appropriate time period to use when looking at today’s state-level gun control laws. As Kostas Moros pointed out, she actually said the opposite. From her concurrence in Bruen:

Second and relatedly, the Court avoids another “ongoing scholarly debate on whether courts should primarily rely on the prevailing understanding of an individual right when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868” or when the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. Here, the lack of support for New York’s law in either period makes it unnecessary to choose between them. But if 1791 is the benchmark, then New York’s appeals to Reconstruction-era history would fail for the independent reason that this evidence is simply too late (in addition to too little). Cf. Espinoza v. Montana Dept. of Revenue, 591 U. S. ___, ___– ___ (2020) (slip op., at 15–16) (a practice that “arose in the second half of the 19th century . . . cannot by itself establish an early American tradition” informing our understanding of the First Amendment).

So today’s decision should not be understood to endorse freewheeling reliance on historical practice from the mid-to-late 19th century to establish the original meaning of the Bill of Rights. On the contrary, the Court is careful to caution “against giving postenactment history more weight than it can rightly bear.”

I will say that the panel did seem skeptical of at least some of New York’s arguments in favor of the multitude of “gun-free zones” imposed by the CCIA; questioning the state’s attorneys about the supposed need for all these sensitive places given that the vast majority of them weren’t off-limits to concealed carry until after the Court struck down the state’s “may-issue” permitting scheme. The state’s response was basically that that just because they weren’t prohibited places before doesn’t mean the legislature doesn’t have the power to make them off-limits to legal gun owners now, but the defendants couldn’t articulate any limiting principle for lawmakers to follow even though SCOTUS made it clear in Bruen that sensitive places are the exception and not the rule.

What happens next? Well, no matter how the panel rules the plaintiffs are likely to appeal directly to the Supreme Court. And it’s entirely possible that the decision will be a mixed bag, rather than an all-or-nothing decision for one side.

My prediction: we are going to get a somewhat favorable ruling on sensitive places, but a generally unfavorable ruling on the application process.

And strategically speaking from the POV of antigun judges, that's probably the combo with the highest chance of SCOTUS saying "meh"… https://t.co/muP3slXEG1

— Kostas Moros (@MorosKostas) March 20, 2023

Moros may be right, but remember that the issue at the heart of Bruen involved the application and permitting process for concealed carry, not where those with permits could do so. The number of sensitive places that New York has imposed in defiance of Bruen‘s edict is important, but that doesn’t make the new licensing standards or application process any less so. The state has tried to replace its unconstitutional “may issue” system with one that’s “shall issue” in name only by continuing to allow issuing authorities the discretion to approve or deny applications based on subjective standards of “good moral character” or the quality of someone’s social media accounts. That should grab the Court’s attention if the Second Circuit panel upholds that portion of the CCIA.

As for when that decision might come down, I don’t think we’ll have to wait too long. This is a request for an injunction, so there is a timeliness issue, and the Supreme Court has already chided the appeals court for not acting quickly enough to address the arguments raised by the plaintiffs. They were certainly fast in posting the audio of today’s oral arguments, so maybe that’s a good sign.

I think this is the fastest I've ever seen the Second Circuit upload oral argument audio https://t.co/NHgJY8jATD

— Rob Romano (@2Aupdates) March 20, 2023

Whether or not the Court is now ready to weigh in itself remains to be seen, but based on today’s hearing I suspect the plaintiffs will find plenty to appeal when the Second Circuit decision comes down.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member