Tomorrow morning the Supreme Court will release orders from last Thursday's conference, and there's a distinct possibility that the Court's decision tossing out the ATF's ban on bump stocks will play a role in the future of one of those cases debated in conference.

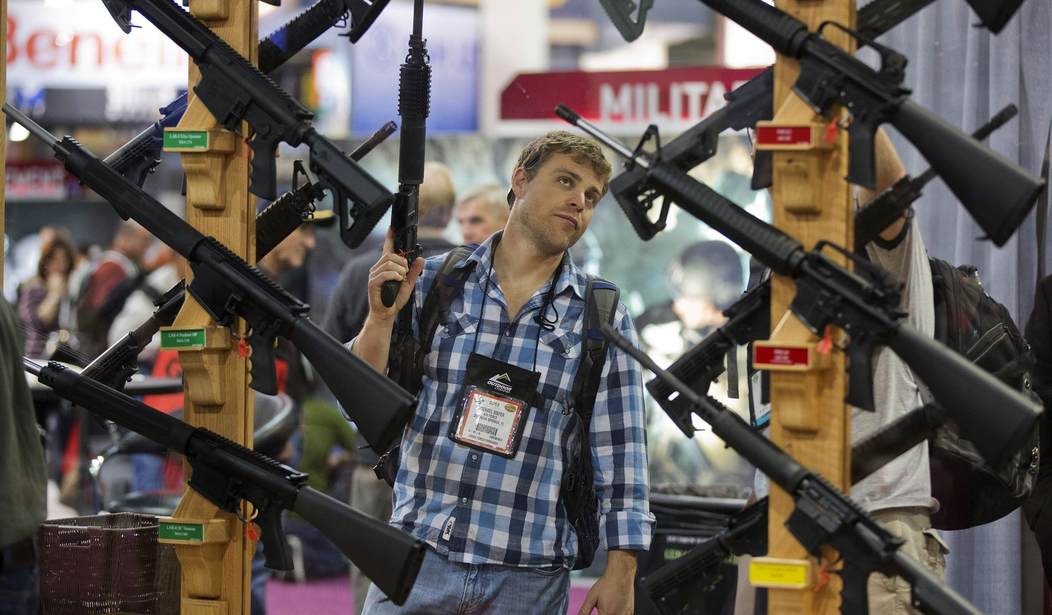

For several weeks now the Court has held on to a cert request filed in a half-dozen challenges to the Protect Illinois Communities Act, which banned hundreds of models of semi-automatic rifles, shotguns, and handguns by labeling them "assault weapons". A U.S. District Judge granted an injunction against the ban, but his decision was overturned by a three-judge panel on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which concluded that the law is likely to pass constitutional muster because the guns that are banned are "like" machine guns and are therefore beyond the scope of the Second Amendment.

On Friday, however, the Supreme Court ruled in Garland v. Cargill that even when a bump stock is attached to a semi-automatic rifle, there's a distinct difference between a full-auto machine gun and a semi-automatic firearm. A bump stock might help increase the rate of fire if used correctly, but it doesn't change the fundamental characteristic of a semi-auto; a separate pull of the trigger is required to release every round of ammunition.

While the Cargill decision didn't discuss the constitutionality of bans on semi-automatic firearms (the case was argued and decided on non-Second Amendment grounds), the ruling still upends a major talking point of the gun control lobby that the Seventh Circuit echoed; there's no meaningful distinction between semi-automatic firearms arbitrarily labeled "assault weapons" and actual machine guns that will empty a magazine with a single pull of the trigger.

The California Attorney General said today that "bump stocks make semiautomatic weapons as dangerous as [] fully automatic weapons," which is interesting because his office argued in our Miller v. Bonta lawsuit that the lack of full-auto capability on semi-auto AR-15s "is not a… pic.twitter.com/D6GrjLLJ92

— Firearms Policy Coalition (@gunpolicy) June 14, 2024

Even the justices who dissented in Cargill recognize the difference, which is damning to the Seventh Circuit's decision in the Illinois gun and magazine ban cases. Justice Sonia Sotomayor acknowledged that semi-automatic rifles are "commonly owned", and her dissent makes it clear that federal law doesn't treat semi-autos and full-autos as one and the same.

Semiautomatic weapons are not “machine guns” under the statute. Take, for instance, an AR–15-style semiautomatic assault rifle. To rapidly fire an AR–15, a shooter must rapidly pull the trigger himself. It is “semi” automatic because, although the rifle automatically loads a new cartridge into the chamber after it is fired, it fires only one shot each time the shooter pulls the trigger.

The labeling of a semi-automatic rifle as an "assault rifle" is cringeworthy, but it's helpful for gun owners in one respect. Even the progressive wing of the Court has rejected the argument that semi-automatic rifles and machine guns are "like" one another in any meaningful way. They might look similar, but they're not the same.

Sotomayor, along with Justice Elena Kagan and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, argue in the dissent that putting a bump stock on a semi-automatic rifle makes it function like a machine gun. The majority opinion did a good job of outlining why the justices are mistaken, but even if Sotomayor was right, it would still mean that a semi-automatic firearm that doesn't have a bump stock attached is not comparable to a machine gun.

I don't know if the Cargill decision makes it more likely that the Supreme Court will accept the plaintiffs' appeal in the Illinois cases, but it does give the Court an obvious route to vacate the Seventh Circuit's decision and remand the cases back to the appellate court for a do-over in light of what the Court held in the bump stock case. SCOTUS can use both the majority and dissenting opinions in Cargill to chide the Seventh Circuit for lumping semi-autos in with machine guns, and direct the panel to correct its error when reconsidering the request for an injunction.

The Court's orders are slated to be released at 10 a.m. Monday morning, and we'll have complete coverage here at Bearing Arms shortly after they're made public. We know that SCOTUS has held on to these cases for several weeks, but we don't know why. I've suspected that the Court has kept these cases because Cargill touches (at least indirectly) on the Seventh Circuit's decision, but we'll know for sure if that's the case less than 24 hours from now.