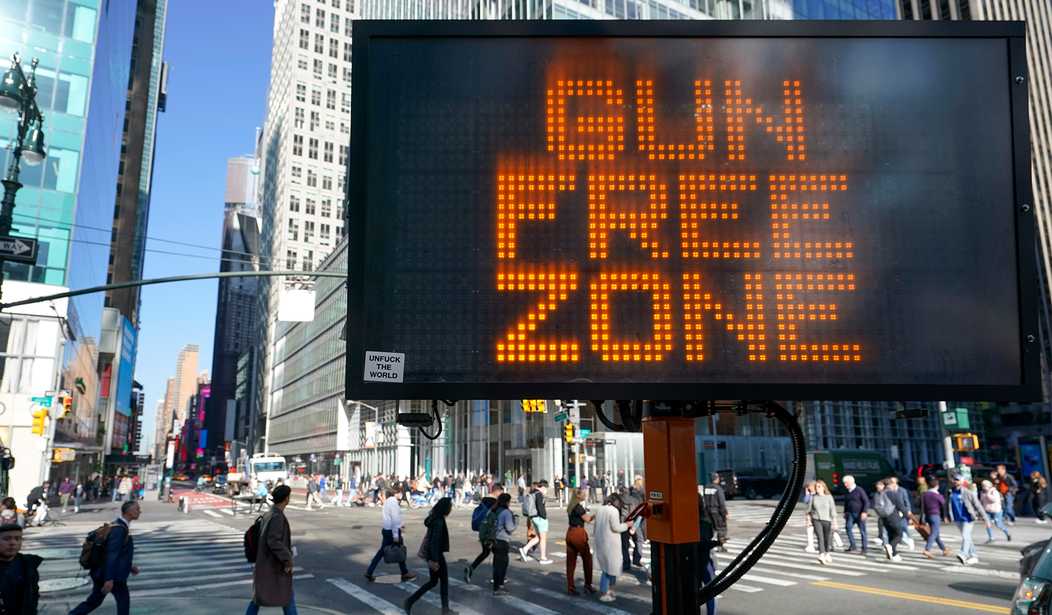

A broad coalition of Second Amendment organizations has filed their opening brief with the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in a case challenging Maryland's nearly exhaustive list of "sensitive places" where lawful concealed carry is banned after a federal judge upheld many of the "gun-free zones" earlier this year.

In his decision, U.S. District Judge George L. Russell III permanently enjoined the state from enforcing its ban on concealed carry in locations where alcohol is served, the prohibition on carrying within 1,000 feet of a public demonstration, and the "vampire rule" that barred concealed carry on all private property unless signage was posted specifically allowing the practice. But Russell also upheld the state's prohibitions on carrying in state parks, mass transit facilities, schools and school grounds, museums, stadiums, healthcare facilities, all government buildings, amusement parks, racetracks, and casinos.

Both the defendants and the plaintiffs appealed Russell's decision, with the state of Maryland seeking the restoration of those "sensitive places" struck down by the district court and the 2A coalition that includes SAF, FPC, and Maryland Shall issue challenging the "gun-free zones" Russell left intact.

In their opening briefs, the Second Amendment advocates argue that Russell relied on "misplaced analogical reasoning and endorsement of the State’s mistaken reliance on far-too-late and otherwise irrelevant historical evidence" to justify the prohibitions that are still in place.

It believed that Maryland may ban firearms virtually anywhere that “serve[s] a vulnerable population,” based on a misreading of Heller’s dicta that restrictions on firearms in “schools” are “presumptively lawful.” But schools are not one of the “relatively few” places where the “historical record” supports a blanket ban on firearms, and Bruen did not authorize analogical reasoning to schools. The district court ignored the critical fact that schools, by reason of their in loco parentis authority over their students, are meaningfully different from Maryland’s litany of supposedly sensitive places. A modern ban on firearms in public locations is not lawful merely because children, vulnerable people, or crowds might be found there.

That's correct. In fact, I'd argue that locations where a vulnerable population might be present but aren't protected by any special security means like magnetometers or armed guards are precisely the places where lawful concealed carry is most important. The owners of private entities like amusement parks, casinos, and racetracks still have the authority to ban concealed carry if they choose, but Maryland has taken that choice away from property owners and have forbidden them from allowing concealed carry even if that's their preference.

The plaintiffs also take issue with the supposed historical analogues cited by Russell.

Compounding its analogical errors, the district court ignored Bruen’s demand for “affirmative[]” evidence of an “enduring,” “representative,” and “comparable tradition of regulation” to justify the challenged law. Almost entirely ignoring that most of Maryland’s locational restrictions ban firearms in places that existed at or before the Founding, the district court held that the State’s historical evidence from Reconstruction and even later is “equally if not more probative” than Founding Era evidence. And it repeatedly relied on motley assortments of outlier jurisdictions from the mid-to-late-19th century that,in addition to being far too late, do not establish a justifying historical tradition of regulation for any of the Carry Bans.

There's a lot of legal debate over which time period in American history is most important when considering a national tradition of firearms. Is it 1791, when the Second Amendment was ratified, or is it 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified and states were told that they couldn't violate the liberties protected by the Bill of Rights anymore than the federal government could?

Gun control advocates and their political allies want 1868 to be the historical standard because there are a few more gun regulations in place than there were in 1791. The problem with that, however, is that the post-Civil War period was also rife with attempts to limit the rights of freed slaves and freedmen; either through explicitly racist laws or statutes that were facially neutral but largely enforced against that population. As the plaintiffs argue:

Focusing on the Founding is critical because historical regulations are “well established” and “enduring” only if they reflect the understandings of the Founders around 1791, not of the Reconstruction Era around 1868. To justify resorting to historical evidence that only began to develop in the mid-to-late 19th century, the district court adopted the view that “historical sources from the time period of the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment are equally if not more probative of the scope of the Second Amendment’s right to bear arms as applied to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.” That holding is wrong, defies controlling precedent, and should be corrected.

... The district court erred by relying on far-too-late historical evidence. And as discussed in detail below, even accepting that those later laws are relevant, the district court erred in relying on a handful of outliers’ restrictive (and nevertheless incomparable) practices that arose in the mid-to-late-19th century when analyzing museums (five laws from 1870 to 1903), healthcare facilities (the same five laws),parks (five laws from 1858 to 1886), and entertainment venues (nine laws from 1869 to 1903). These relatively few, late-in-time restrictions cannot justify the Carry Bans, each regulating locations well known to the Founders.

A handful of laws, many of which were adopted decades after the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, cannot be the basis for a national tradition of banning guns from these locations, but that's exactly what Russell relied on in upholding many of the state's "gun-free zones". And unfortunately, the Fourth Circuit may very well adopt Russell's reasoning as its own. The appellate court has already upheld Maryland's ban on so-called assault weapons and its handgun licensing law this year, and I suspect they'll do the same with the state's "sensitive places," despite the strength of the plaintiffs' arguments. The real question is what SCOTUS will do with the case when it reaches the nine justices in a year or so.