The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals could have held on to the lawsuit challenging Maryland's default ban on concealed carry on private property open to the public until after the Supreme Court issued its opinion on Hawaii's "vampire rule," but instead the appellate court issued its decision striking down the Maryland statute while SCOTUS was hearing oral arguments in Wolford v. Lopez on Tuesday.

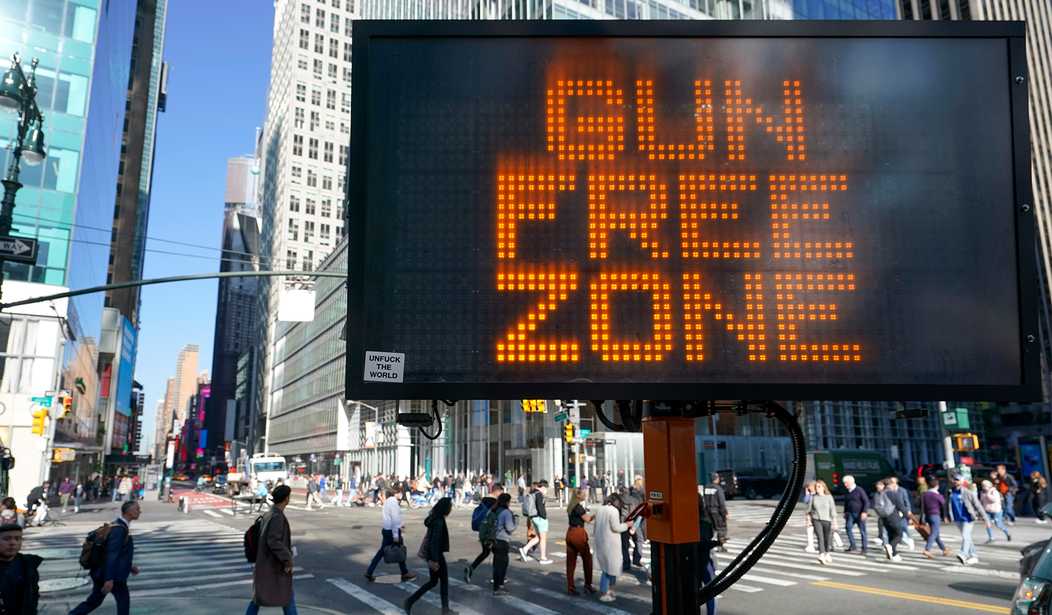

Unfortunately, that's the only good part of the Fourth Circuit's decision, which also upheld Maryland's designation of all government buildings, public transportation, "school grounds," any place within 1,000 feet of a public demonstration, state parks, museums, healthcare facilities, stadiums, racetracks, amusement parks, casinos, and locations that sell alcohol as "gun-free zones."

In doing so, the Fourth Circuit purported to laid out its framework for determining whether a place can be considered "sensitive" enough where the right to carry can be prohibited. In reality though, the majority of the three-judge panel seemed to decide on an ad hoc basis that virtually every one of Maryland's "gun free zones" should be upheld.

The panel did no historical analysis at all of the ban on firearms in government buildings. Instead, it stated that "guidance from the Supreme Court is more than sufficient" to uphold the prohibition. The ban on carrying on public transportation was upheld under the proprietary property doctrine; which essentially says the government, acting as proprietor, has the authority to manage its internal operation just like a private property owner does.

The ban on carrying on school grounds was similarly upheld without any historical analysis, with the panel concluding that the Supreme Court's dicta about schools being sensitive places applies to school grounds as well.

The majority concluded that historic laws banning "unlawful assemblies" suffice to ban concealed carry within 1,000 feet of a public assembly, even though the law can entrap individuals who aren't even taking part in that assembly, lawful or otherwise.

Maryland's ban on concealed carry in all parks was upheld on the basis of some cities adopting gun prohibitions in urban parks in the mid-to-late 19th century, with the panel's majority declaring "the same logic applies to Maryland’s limitations on guns in forests."

Here, we rely on the Supreme Court’s teaching that a challenged regulation can survive a Second Amendment challenge even where it does not precisely match its historical precursors.

Perhaps the most absurd conclusion was the panel's decision that bans on concealed carry in places where alcohol is served is 2A compliant because some colonial-era laws forbade serving liquor to members of the militia when they actively serving, along with a handful of 19th century laws that “prohibited intoxicated persons from carrying firearms.” Though none of those laws prohibited carrying guns in places where alcohol is served, the majority concluded that there is a “well-established tradition of prohibiting firearms at crowded places.”

If that's the case, then the Bruen decision is essentially moot, and guns can be banned in virtually all places that are open to the public. But the Supreme Court explicitly stated in Bruen that "there is no historical basis for New York to effectively declare the island of Manhattan a “sensitive place” simply because it is crowded and protected generally by the New York City Police Department;" a statement utterly ignored by the majority of the Fourth Circuit panel.

Judge G. Steven Agee agreed with the majority about gun bans in government buildings and healthcare facilities, as well as overturning the "vampire rule." Otherwise, though, the judge believes "the majority opinion simply fails to follow how the Supreme Court has directed courts to consider the historical tradition of firearm regulation when examining whether a particular law violates the Second Amendment right to carry arms in public."

At bottom, the Supreme Court has made clear that the historical analogues from which courts discern the principles on which the how and why of firearms regulations are compared originate in the Founding Era, not later. The district court’s decision and the majority opinion grossly misread Bruen to treat Reconstruction-era and later firearms regulations as relevant historical analogues to assess whether the modern challenged laws are constitutional.

More troubling still, for many of the challenged Maryland provisions, a smattering of mid-to-late 19th century and later laws serve as the only historical analogues on which the majority opinion pins its analysis. That diversion only further attenuates its conclusions from Bruen’s mandate to understand the Second Amendment’s scope based on its widespread meaning at the Founding.

Agee's dissent is worth reading in full, and I suspect it will be quoted extensively when the plaintiffs appeal today's decision to the Supreme Court. These challenges, known as Kipke v. Moore and Novotny v. Moore, would be logical followups for the Court to take after it issues its decision in Wolford v. Lopez, though that upcoming opinion may contain enough language to rebut the Fourth Circuit's conclusion and lead to the appellate court's decision being vacated and remanded for a do-over instead.

During today's oral arguments the Court's conservative majority once again made it clear that the Second Amendment is not a second-class right, but that's exactly how the Fourth Circuit is treating it. By eviscerating the right to carry in public, the panel's majority has turned a fundamental right into little more than faded words on a old piece of paper, and it's up to the Supreme Court to right this wrong.