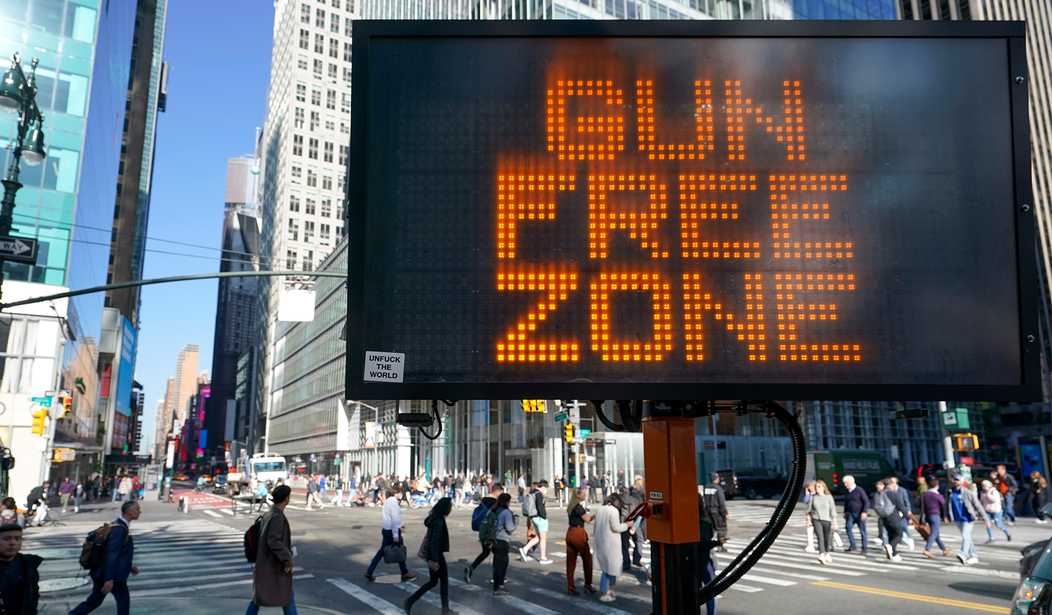

For decades, New Yorkers who possessed a concealed carry license were free to lawfully carry a firearm almost everywhere in the state, including most businesses. If a property owner wanted to bar lawful carry they could do so, but they had to post signage to that effect. It was a system that worked without complaint, but in the wake of the Bruen decision New York lawmakers decided if they couldn’t deny most residents a license to carry, they could at least prohibit them from carrying in most publicly-accessible places. Among the many new “gun-free zones” established by the state legislature was a default ban on carrying on private property unless the property owners posted signage specifically allowing the practice.

That policy, derided as the “vampire rule” by many Second Amendment advocates, not only flipped the status quo in New York, but has been adopted by several other states over the past 18 months. The rule hasn’t fared well in court, however, and New York’s provision is on hold after a federal judge recently concluded that the default ban is at odds with the text, history, and tradition of the right to keep and bear arms.

In a new op-ed at The Hill, law professors Ian Ayers and Frederick Vars call the opinion “deeply flawed,” arguing that “there is no constitutional right to a presumption that a private owner welcomes firearms until the owner announces otherwise.”

An individual’s right to bear arms ends at someone else’s property line. A business owner can choose to exclude people who bear arms — just as they can limit their invitations to people without pets or people who are wearing shoes.

And how do they do that, generally speaking? By posting a sign that says pets are not allowed or “no shirt, no shoes, no service”, right? Similarly, private property owners can still exclude people who bear arms even without the “vampire rule”; they just have to post a sign alerting gun owners to that fact.

Ayers and Vars brush over that inconvenient fact, instead blithely asserting that times change, and even if the vampire rule has no historical analogue in the past, there’s no reason it shouldn’t be adopted today.

The evolution of implied invitations to enter private property has also applied to gun use. Traditionally, armed strangers were permitted to enter onto unimproved rural land to hunt — unless the owner posted “No Trespassing” signs along the land’s perimeter. But now half the states have flipped the presumption so that it is trespassing to hunt on private property without the owner’s consent.

The law of implied invitations evolves because social norms change over time. Customers generally understand that, by default, they are not allowed to bring their (non-service) animals into a hotel room or a restaurant. They must look for “pet-friendly” or “pets allowed” establishments. But customs can change, and it is reasonable for the law to reflect that change.

Both the district court that heard the Antonyuk case and the Second Circuit panel that heard its appeal ruled that comparing the vampire rule to “no trespassing signs” is a non-starter, with the district court finding that prohibiting “some people from openly carrying rifles on other people’s farms and lands in 19th century America is hardly analogous to barring all license holders from carrying concealed handguns in virtually every commercial building now.”

The Second Circuit panel, meanwhile, declared that “because over 91 percent of land in New York state is privately held, the restricted location provision would turn much of the state of New York into a default no-carriage zone,” something that would be entirely at odds with the right to carry a firearm in public.

Given that most spaces in a community that are not private homes will be composed of private property open to the public to which § 265.01-d applies, the restricted location provision functionally creates a universal default presumption against carrying firearms in public places, seriously burdening lawful gun owners’ Second Amendment rights. That burden is entirely out of step with that imposed by the proffered analogues, which appear to have created a presumption against carriage only on private property not open to the public.

In sum, the State’s analogues fail to establish a National tradition motivated by a similar “how” or “why” of regulating firearms in property open to the public in the manner attempted by § 265.01-d. Accordingly, the State has not carried its burden under Bruen.

Ayers and Vars contend that New York still has a way of enacting the same prohibition that the courts have enjoined; “enacting a new requirement that businesses holding themselves open to the public affirmatively state whether or not they want patrons entering their property to carry weapons.” That, the law professors maintain, would leave that decision up to the property owner, not the government “and so there is no government restriction on the right to bear arms, or even a finger on the scale for or against concealed carry.”

Well, except for the fact that the New York government would be putting that provision in place with the express intent of encouraging private property owners to ban concealed carry in their publicly accessible spaces. Again, property owners already possess the right to prohibit lawful carry on their premises. They just have to post a sign to that effect, and that should be the default when we’re talking about the exercise of a fundamental, individual right. If we don’t want solicitors we post a sign to that effect. If we don’t want pets in our stores we post a sign to that effect. Why should the right to keep and bear arms be treated any differently?

Because far too many people, including Ayers and Vars, still insist on treating the Second Amendment as if it’s a second-class right (if not merely a privilege to be doled out by the State), that’s why. The Second Circuit reached the correct conclusion when it comes to the vampire rule, but it’s the Supreme Court that will have to drive a stake through its heart when it finally gets ahold of Antonyuk and its associated cases,